There is just something about Stephen King’s writing that is like the feeling I get after having been out there, working in the real world, after a hard day, fighting deadlines and traffic, often snow, lots of that, then finally coming home. I get all toasty, feet warm, comfortable, with his voice in my head.

I soon settled in and listened as he told me the story of Doctor Sleep.

Having read The Shining for the first time just last year, it was still fresh in my mind, so where King took Danny Torrance here, made sense to me, felt right. But King is not a man of few words and so there are others here; the good and the bad, with histories of their own to share. It is a good story.

I know that there are many who bemoan King’s loquaciousness but I love it. Cliché, perhaps, but this mans spin a good yarn.

I was hooked from the get go. I am not going to tell you this story, King should.

Listen Up!

2

2

Mo Hayder delivers the most thought provoking thriller I have ever encountered. Set in 1990 Tokyo with roots that take you back to the 1937 Nanking massacre, this account is positively chilling.

Three voices have entered my head.

Grey: is a personally troubled, young student from London, with a highly unstable past and a vested interest in her research of war atrocities, most notably the 1937 Nanking Massacre. She has come to Tokyo in search of Shi Chonming, a Nanking survivor, who Grey believes also possesses a lost piece of film. We learn more about her and her obsession with Chongming as the story advances, peeling back the layers slowly as one might an onion.

It is 1990

Shi Chongming stood in the doorway, very smart and correct, looking at me in silence, his hands at his sides as if he was waiting to be inspected. He was incredibly tiny, like a doll, and around the delicate triangle of his face hung shoulder, length hair, perfectly white, as if he had a snow shawl draped across his shoulders.

I’m not very good at knowing what other people are thinking, but I do know that you can see tragedy, real tragedy, sitting just inside a person’s gaze. You can almost always see where a person has been if you look hard enough. It had taken me such a long time to track down Shi Chongming. He was in his seventies, and it was amazing to me that, in spite of his age and in spite of what he must feel about the Japanese, he was here, a visiting professor at Todai, the greatest university in Japan.

Chongming: We hear his voice as he remembers his time in Nanking:

We slept fitfully, in our shoes just as before. A little before dawn we were woken by a series of tremendous screams. It seemed to be coming from only a few streets away and it was distinctly a woman’s voice. I looked across at Shujin. She lay absolutely rigid, her eyes fixed on the ceiling, her head resting on the wooden pillow. The screaming continued for about five minutes, getting more desperate and more horrible, until at last it faded to indistinct sobs, and finally silence. Then the noise of a motorcycle on the main street thundered down the alley, shaking the shutters and making the bowl of tea on the bed-stand rock.

At the base of the tree the handcart had been set upright, our blankets and belongings scattered around it. A set of muffled tracks led away into the trees. I swerved into them, my eyes watering, ducking as the bare branches whipped against my face. The track led on for a few more yards, then changed. I skidded to a halt, my heart racing; the tracks had become wider here. An area of disturbed snow stretched around me for several feet, as if she had fallen to the ground in pain. Or as if there had been a struggle. Something lay half buried at my feet. I fell to a crouch and snatched it up, turning it over in my hands. A thin piece of tape, frayed and torn. My thoughts slowed, a terrible dread creeping over me. Attached to the tape were two Imperial Japanese Army dogtags.

In direct contrast to the atrocities of this story lay Hayder’s breathless, lyrical prose. She paints vivid scenes with her words.

In the distance, black against the sky, a behemoth of tinted glass supported by eight massive black columns rocketed up above all the other skyscrapers. Four gigantic black marble gargoyles crouched on each corner of the roof, gas streams in their mouths blowing fire jets fifty feet out until the sky seemed to be on fire.

Bolted by a mechanical arm to the crown of the skyscraper there was a vast cut-out of a woman sitting on a swing. Marilyn Monroe. She must have been thirty feet from her white high heels to her peroxide hair, and she swung back and forward in fifty foot arcs, molten neon flickering so that her white summer dress appeared to be blowing up above her waist. That’s Some Like It Hot. The club where we work.

It is here where Grey finds work and makes a sinister connection, one that may help her convince Chongming to let her see the film she so desperately needs to see.

Hayder does not just paint great backdrops; she also introduces us to characters that slither deep into our consciousness.

In the centre of the gang was a slim man in a black polo- neck, his hair tied in a ponytail. He was pushing a wheelchair, in which sat a diminutive insectile man, fragile as an ageing iguana. His head was small, his skin as dry and crenulated as a walnut, and his nose was just a tiny isosceles, nothing more than two shady dabs for nostrils – like a skull’s. The wizened hands that poked out from his suit cuffs were long and brown and dry as dead leaves.

Hayder deftly controls the pace at which both these narratives unfold, tension building with each turn of the page. I was riveted, unwilling just then, to leave behind the events of 1990, and but a few pages later, so equally reluctant to leave Nanking.

Iris Chang: Author of The Rape of Nanking, to whom Hayder has dedicated this book, whose bravery and scholarship first lifted the name of Nanking out of obscurity.

This is her voice:

“I want the rape of Nanking to penetrate into public consciousness. Unless we truly understand how these atrocities can happen, we can’t be certain that it won’t happen again.

If the Japanese government doesn’t reckon with the crimes of its wartime leaders, history is going to leave them as tainted as their ancestors. You can’t blame this generation for what happened years ago, but you can blame them for not acknowledging these crimes.

Denial is an integral part of atrocity, and it’s a natural part after a society has committed genocide. First you kill, and then the memory of killing is killed.”

I want to hear more.

3

3

Mo Hayder delivers the most thought provoking thriller I have ever encountered. Set in 1990 Tokyo with roots that take you back to the 1937 Nanking massacre, this account is positively chilling.

Three voices have entered my head.

Grey: is a personally troubled, young student from London, with a highly unstable past and a vested interest in her research of war atrocities, most notably the 1937 Nanking Massacre. She has come to Tokyo in search of Shi Chonming, a Nanking survivor, who Grey believes also possesses a lost piece of film. We learn more about her and her obsession with Chongming as the story advances, peeling back the layers slowly as one might an onion.

It is 1990

Shi Chongming stood in the doorway, very smart and correct, looking at me in silence, his hands at his sides as if he was waiting to be inspected. He was incredibly tiny, like a doll, and around the delicate triangle of his face hung shoulder, length hair, perfectly white, as if he had a snow shawl draped across his shoulders.

I’m not very good at knowing what other people are thinking, but I do know that you can see tragedy, real tragedy, sitting just inside a person’s gaze. You can almost always see where a person has been if you look hard enough. It had taken me such a long time to track down Shi Chongming. He was in his seventies, and it was amazing to me that, in spite of his age and in spite of what he must feel about the Japanese, he was here, a visiting professor at Todai, the greatest university in Japan.

Chongming: We hear his voice as he remembers his time in Nanking:

We slept fitfully, in our shoes just as before. A little before dawn we were woken by a series of tremendous screams. It seemed to be coming from only a few streets away and it was distinctly a woman’s voice. I looked across at Shujin. She lay absolutely rigid, her eyes fixed on the ceiling, her head resting on the wooden pillow. The screaming continued for about five minutes, getting more desperate and more horrible, until at last it faded to indistinct sobs, and finally silence. Then the noise of a motorcycle on the main street thundered down the alley, shaking the shutters and making the bowl of tea on the bed-stand rock.

At the base of the tree the handcart had been set upright, our blankets and belongings scattered around it. A set of muffled tracks led away into the trees. I swerved into them, my eyes watering, ducking as the bare branches whipped against my face. The track led on for a few more yards, then changed. I skidded to a halt, my heart racing; the tracks had become wider here. An area of disturbed snow stretched around me for several feet, as if she had fallen to the ground in pain. Or as if there had been a struggle. Something lay half buried at my feet. I fell to a crouch and snatched it up, turning it over in my hands. A thin piece of tape, frayed and torn. My thoughts slowed, a terrible dread creeping over me. Attached to the tape were two Imperial Japanese Army dogtags.

In direct contrast to the atrocities of this story lay Hayder’s breathless, lyrical prose. She paints vivid scenes with her words.

In the distance, black against the sky, a behemoth of tinted glass supported by eight massive black columns rocketed up above all the other skyscrapers. Four gigantic black marble gargoyles crouched on each corner of the roof, gas streams in their mouths blowing fire jets fifty feet out until the sky seemed to be on fire.

Bolted by a mechanical arm to the crown of the skyscraper there was a vast cut-out of a woman sitting on a swing. Marilyn Monroe. She must have been thirty feet from her white high heels to her peroxide hair, and she swung back and forward in fifty foot arcs, molten neon flickering so that her white summer dress appeared to be blowing up above her waist. That’s Some Like It Hot. The club where we work.

It is here where Grey finds work and makes a sinister connection, one that may help her convince Chongming to let her see the film she so desperately needs to see.

Hayder does not just paint great backdrops; she also introduces us to characters that slither deep into our consciousness.

In the centre of the gang was a slim man in a black polo- neck, his hair tied in a ponytail. He was pushing a wheelchair, in which sat a diminutive insectile man, fragile as an ageing iguana. His head was small, his skin as dry and crenulated as a walnut, and his nose was just a tiny isosceles, nothing more than two shady dabs for nostrils – like a skull’s. The wizened hands that poked out from his suit cuffs were long and brown and dry as dead leaves.

Hayder deftly controls the pace at which both these narratives unfold, tension building with each turn of the page. I was riveted, unwilling just then, to leave behind the events of 1990, and but a few pages later, so equally reluctant to leave Nanking.

Iris Chang: Author of The Rape of Nanking, to whom Hayder has dedicated this book, whose bravery and scholarship first lifted the name of Nanking out of obscurity.

This is her voice:

“I want the rape of Nanking to penetrate into public consciousness. Unless we truly understand how these atrocities can happen, we can’t be certain that it won’t happen again.

If the Japanese government doesn’t reckon with the crimes of its wartime leaders, history is going to leave them as tainted as their ancestors. You can’t blame this generation for what happened years ago, but you can blame them for not acknowledging these crimes.

Denial is an integral part of atrocity, and it’s a natural part after a society has committed genocide. First you kill, and then the memory of killing is killed.”

I want to hear more.

Gerald Francis McCabe, he thought. That’s who I was-

He was struck from every angle and with every measure of force.

Blood bloomed thick around him. Tick did not resurface.

Nearby, beer bottles clicked, cigars burned, and significant money exchanged hands.

Six heroin addicts, strangers to each other, all from the seedy underbelly of Miami, find themselves stranded on a deserted island in the Florida Keys. They are jonesing for a fix and the only foreseeable way to get that is to swim to the next island.

But they are being watched, from a yacht anchored off shore, in open water.

No one is coming to your aid.

We have ensured this.

These are shallow waters, where thought can run deep, but do not think yourself safe. You are fodder.

So get that adrenaline flowing, this one has an unapologetic, relentless pace. Only a hundred yards to go……….move!

3.4 stars. We should keep an eye on this young man.

Not recommended for the faint of heart.

"All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing."

I remember a time not so long ago, at least not by my demographic. A time when, what happened at home, stayed at home You did not hang out your dirty laundry.

People did not talk about the unsavoury. It wasn’t proper and it was not accepted. Honour your father and your mother. Everybody has secrets, but Only bad girls go to jail.

Backwoods noir, I know it and here it is.

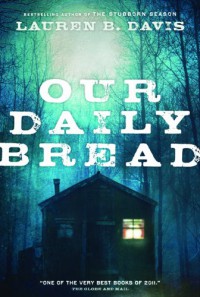

Inspired by the true story of the Goler Clan of Nova Scotia, Our Daily Bread tells the story of The Erskines, who live on North Mountain, in poverty, secrecy and isolation. They deal in moonshine, marijuana and most recently the making and moving of meth.

Albert Erskine is one of their clan, but he is far from comfortable in his own skin or theirs. He yearns for a better life, a way to distance himself from these woods, the elders, their secrets.

Davis quickly brings the reader into the dark heart of these secrets without ever resorting to sensationalism. A glimpse is all that is needed.

Six year old club-footed Brenda, one of Lloyd’s kids, stood on an old bucket and looked in a back window. She wore a boy’s jacket over a filthy pink nightgown, a pair of rubber boots several sizes too large, to accommodate her twisted left foot. She’d been in need of a bath several weeks ago. Albert knew what she was probably seeing in there, and he knew if she got caught she’d get a worse beating than he just got. If he called out he’d just scare her and she’d make a noise and then they’d both be in for it. He should just walk away and let whatever was going to happen go right on and happen. Erskines don’t talk and Erskines better mind their own fucking business. She turned then and looked at him tears pouring down her face.

Time peeled away, fled backwards and Albert was six years old again, his mouth full, gagging, the stench and sound of moans, his own flesh tearing……..bile rushed acidly into his mouth. His hands shook. His knees shook. He turned away. Spit. Spit again. One of these days he was going to do it. He’d get his rifle and put and end to the Erskines, all of them.

Gideon, the town closest to North Mountain is full of God fearing people who shun The Erskine clan and the people of North Mountain. They believe them to be beyond salvation. Even so the people in Gideon have their own problems. Take Tom Evans, his marriage is in trouble, leaving his children Ivy and Bobby at odds, looking for their own solace.

When Albert Erskine, comes down off the mountain to fish, he runs into Tom’s teenage son Bobby, and an unlikely friendship develops. A friendship that is destined to set the people of North Mountain and Gideon on a collision course. One with devastating results.

Dorothy Carlisle is an independent minded widow who runs a local antique shop in Gideon. She is following a tradition, one once shared with her late husband, one of taking boxes of provisions: clothes, food, books and such, up to the mountain and leaving them in a secluded spot, hopefully, for the children to find.

Part of her very much did not want to hear the sound again. A voice in her head told her to get back in the car as quickly as possible, and lock the doors. She was aware of her own heartbeat, and of the blood pulsing in her veins. Crickets. A mosquito near her ear, which she forced herself not to swat. And then…. “Mmmuhuuh….mmmuhhaaaa”…..Bestial, but not the sound of an animal. Human. “Uuuhhuhhh.” Human made inhuman. A sort of low keening – bereft even of the hope anyone might hear. Dorothy’s skin prickled and tightened. The sound held no threat, but seemed to echo from an abyss of despair. Her horror was not of something red in tooth and claw, or even fist and blade. Rather, she recoiled from understanding. She feared for her soul if it peered into that abyss. As though under some hideous enchantment, Dorothy stared at her own trembling hand, unable to move. “Oh God, oh God, oh God. Protect us.” The sound, the cry, came again then. Mourning made manifest. Such grief was surely as isolating, as solitary as any cell of stone or steel, as any nail and cross. Left to its own devices it would suck the entire world into the centre of its tarry core. It was alone out there.

This is the real deal. Read it.

I am so not the target audience for this story.

I mean it’s a western.

Right?

Still the cover art kept pulling at me

It’s the 1850’s, gold rush, California

And the Sisters Brothers are two killers for hire,

on the trail; on a job.

And I thoroughly enjoyed it, from the get go.

Charlie Sisters has the lead here, but it is Eli that will take you there.

And tell you all about his horse, poor Tub, and the women he meets along the way.

How he feels; what he wants; how he sees things, love and some alarmingly, gruesome grub.

It is all about the journey.

I loved his voice; his simple, sardonic; hard, yet warm hearted slant.

Shoot Outs, Indians, Gold.

Blood and gore and greed;

Chilling, veterinarian like solutions;

No worries, they have a toothbrush.

I am still unsure how exactly; but Patrick deWitt took me on one helluva ride.

giddyup!

Gerald Francis McCabe, he thought. That’s who I was-

Gerald Francis McCabe, he thought. That’s who I was-He was struck from every angle and with every measure of force.

Blood bloomed thick around him. Tick did not resurface.

Nearby, beer bottles clicked, cigars burned, and significant money exchanged hands.

Six heroin addicts, strangers to each other, all from the seedy underbelly of Miami, find themselves stranded on a deserted island in the Florida Keys. They are jonesing for a fix and the only foreseeable way to get that is to swim to the next island.

But they are being watched, from a yacht anchored off shore, in open water.

No one is coming to your aid.

We have ensured this.

These are shallow waters, where thought can run deep, but do not think yourself safe. You are fodder.

So get that adrenaline flowing, this one has an unapologetic, relentless pace. Only a hundred yards to go……….move!

3.4 stars. We should keep an eye on this young man.

Not recommended for the faint of heart.

Sharp Objects

Shudder!

Shudder!This is one seriously disturbing, creepy, little story, cut with a gothic edge.

It is also the second Gillian Flynn I have read and it is true, I believe her books are best read blind.

This one I delved into with next to no knowledge of the story. Perfect.

With Camille Preaker, Flynn gives us an unlikely heroine and a narrator to care about. Camille told me this story, deftly uncovering the details of creep over time. This effectively left me unsure that I even wanted to know more and quite unable to stop myself from reading on. No question this is one of sickest, most disturbing Mother/Daughter relationships I have ever encountered. It puts the D in dysfunctional.

“Now it cuts like a knife

But it feels so right

Ya it cuts like a knife

But it feels so right”

Who would believe that this is a debut novel?

It blew my socks off.

Well, peeled them off actually, with short, sure strokes.

Trust me; let Flynn tell you this story.

It is best that way.

This book, while brimming with possibility, is a promise unfulfilled.

This book, while brimming with possibility, is a promise unfulfilled.A young woman, Lucy, returns from Japan to her upstate New York home, actually a Victorian mansion by The Lake of Dreams, a place from which she has distanced herself since her father’s death. As she adjusts to the changes about her she finds some old documents in a locked window seat, documents that soon reveal an unknown family history.

Having once discovered the old documents Lucy then shares her find with her Mother who just happens to remember that over twenty years ago she found an old baby blanket, with a note that matches the handwriting on the documents. A beautiful blanket with a pattern on it that was tucked away twenty years ago and not thought of again until just now. And so the plot advances. Lucy becomes obsessed with the long lost owner of the documents and the pattern woven into the blanket which just happens to be a recurring pattern in a stained glass window that her once upon a time boyfriend Keegan Fall is restoring. Naturally this discovery leads her to more stained glass windows and convinces her that the owner of the documents could very well be the woman depicted in the windows, which of course take her off to find out more about the artist. Biff, boom, bang more connections are made.

While all of this is happening Lucy is coming to terms with the guilt she has carried all these years about her father’s death and struggling with her newly awakened feelings for her long lost love Keegan and worrying about her mixed feelings for her current fellow, Yoshi, due to arrive any day now from Japan. Good lord can this plot get any weaker? Spoiler alert……. it can.

Beyond all the astoundingly weak plot forwarding devices, the biggest problem I had with this is that the protagonist does not act the way a real person would, ever. She is in good company though as most of the other characters are equally unbelievable. Case in point - Lucy learns that her father’s brother Art was complicit in her dad’s death. He was there out on the lake arguing with him that fateful night. Heated words are exchanged and Art pushes his brother who falls out of the boat. Art tries to find him and when he is unsuccessful just leaves and never mentions this to anyone. So Lucy vandalizes his store and then shares this information with her family. There is no outrage, just disbelief from her brother and a quiet acceptance from her Mother. Everybody remembers how kind Art has been over the years since his brother’s death. Seriously……that’s it.

I have been thinking about time well spent. That was not the case here.

Age vitam plenissime

Take a walk in the park

perhaps of an evening,

moonlight dancing lightly

through the swaying branches of the willow,

reflected off the water,

where the heron feeds,

Illuminating our path.

There is a slight breeze

a welcome silence

later we will have a fire

and listen to the music of the night.

I am humbled to remember that poetry is after all everywhere. It envelopes us. It is in the words we read and those we speak to each other.

It is in the very air I breathe, deep and slow.

I love poetry so it seems that I was destined to find

S. Penkevich’s review of this work.

If you have but a moment, then leave this page at once and read his review.

It is after all what brought me here.

And so I sail, around the room, while bits and pieces of this cling to me. They move about my head.

I am a sinner, not a scholar and rearrange them as it pleases me.

They clutter my windshield and call forth my senses.

I cannot seem to stop. Perhaps this is disrespectful

but I think not.

How easy he has made it for me to enter here,

to sit down in a corner;

cross my legs like his, and listen.

I walk through the house reciting it

and leave its letters falling

through the air of every room.

I listen to myself saying it,

then I say it without listening,

then I hear it without saying it.

And later when I say it to you in the dark,

you are the bell,

and I am the tongue of the bell, ringing you

But today I am staying home,

standing at one window, then another,

or putting on a jacket

and wandering around outside

or sitting in a chair

watching the trees full of light- green buds

under the low hood of the sky.

And when I begin to turn slowly

I can feel the whole house turning with me,

rotating free of the earth.

the sun and the moon in all the windows

move, too, with the tips of my fingers

this is the wheel I just invented

to roll through the rest of my life

Why do we bother with the rest of the day,

the swale of the afternoon,

the sudden dip into evening,

This is the best-

throwing off the light covers,

feet on the cold floor,

and buzzing around the house

Until the night makes me realize

that this place where they pace and dance

under colored lights,

is made of nothing but autumn leaves,

red, yellow, gold,

waiting for a sudden gust of wind

to scatter it all

into the dark spaces

beyond these late- night, practically empty streets.

Then I remove my flesh and hang it over a chair.

I slide it off my bones like a silken garment.

Such is life in this pavilion

of paper and ink

where a cup of tea is cooling,

where the windows darken then fill with light.

A book like this always has a way

of soothing the nerves,

quieting the riotous surf of information

that foams around my waist.

But it is hard to speak of these things

how the voices of light enter the body

and begin to recite their stories

how the earth holds us painfully against

its breast made of humus and brambles

how we who will soon be gone regard

the entities that continue to return

greener than ever, spring water flowing

through a meadow and the shadows of clouds

passing over the hills and the ground

where we stand in the tremble of thought

taking the vast outside into ourselves.

Still, let me know before you set out,

come knock on my door

and I will walk with you as far as the garden.

My fingertips thirsty, absorb this ink and intoxicated,

leave my stain all over these pages.

Thank you Billy!

All of the words in italics are Billy’s.

They have moved themselves around shamelessly to feed my unbridled pleasure.

Woot!

Woot!Love so much Love is what I have for this writer. He’s a guilty little pleasure. I have been known to lick my lips, settle in my chair, feet up, chilled Chablis close at hand and over indulge. This one is so damn delicious.

If you know Barclay at all then you know he writes thrillers, of the domestic variety. The kind of thing that could happen to you or me does happen in them.

I cannot seem to get enough and this is my hands down favourite so far. I could not put it down!

I’m getting me another Linwood Barclay!

Glutton that I am.

"Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s."

Brandon Sanderson has hit a home run here in this awesome world of chalk, just sick with possibility. He drops you into this world of chalk drawings that come to life, possess power and threaten the main protagonists, who also duel and defend in chalk.

These protagonists, the people of whom I speak, are interesting; possess a depth that contradicts Sanderson’s sparse prose. I found it easy to connect with and care about them.

But they are at risk, under attack from the wild chalkings.

The concept is so simple. The future is wide open and invites complexity.

Ben McSweeney’s illustrations are spot on, deftly portraying the rules of battle, bursting with Sanderson’s positively plump pace of potential.

The Rithmatist is sure to spark discussion, invite lively, animated debate, especially among those strategic thinkers, those denizens of debauchery.

I love that there are so many excellent options available to our young readers today. They own tomorrow.

You can too, just gather your knowledge; draw your lines of vigour and forbiddance. Get in your circle, imagine well, your chalkings, then plan and maintain your offense.

New rithams are possible.

These are the difficult reviews to write. When you just can’t connect with a story that most everyone else seems to love. This one has all the right elements.

These are the difficult reviews to write. When you just can’t connect with a story that most everyone else seems to love. This one has all the right elements.1926 New York with speakeasies, flappers, glitter and temperance. Seventeen year old Evie O’Neill has just arrived to stay with her Uncle who runs The Museum of the Creepy Crawlies. When a body, branded with a cryptic symbol is found her Uncle, who has a well informed obsession with the occult, is called in and Evie tags along. But Evie has secrets of her own, special powers that allow her to divine certain things about people.

She is also a party girl in a city teeming with life; other stories unfold, other secrets emerge. Oh and something dark and evil has awakened, armed with a sinister agenda. Naughty John has come home, whistling his own little ditty.

Most of the main characters in this story are about the same age as Evie but have a history, feelings that bely their young age. Something doesn’t fit. Memphis, a poetry writing, numbers runner, was the only character that bled through the pages to reach me; I thought he was wonderful, touched by a thoughtful pen. The rest are cardboard cut-outs, restored images of a time and place. Bray does an excellent job in painting atmospheric scenes, both shiny and grim. There just images though, ideas pulled wet from a well, then groomed and channelled to promise future tales, pushed together, edges furled, some left flapping; bound by the thin thread of a story. For me there was no harmony, not as though Bray hit the wrong notes exactly, more like she never quite found the right ones. It felt more assembled than written, nothing flowed or coalesced and in the end I felt removed and yes, manipulated.

Perhaps most unsettling of all, my daughter absolutely loved this book. Over time and after many a shared stroll through many a page, bound and moved by a myriad of words, I have come to trust and respect her opinion. And while our interests may take us in different directions, more often then not, when we meet, we agree. We may not be completely in sync, but we are at least in the same ball park. Not here. Not even the same playing field.

Ouch! It must be me. No worries…….books will find their own home.

I am so not the target audience for this story.

I am so not the target audience for this story.I mean it’s a western.

Right?

Still the cover art kept pulling at me

It’s the 1850’s, gold rush, California

And the Sisters Brothers are two killers for hire,

on the trail; on a job.

And I thoroughly enjoyed it, from the get go.

Charlie Sisters has the lead here, but it is Eli that will take you there.

And tell you all about his horse, poor Tub, and the women he meets along the way.

How he feels; what he wants; how he sees things, love and some alarmingly, gruesome grub.

It is all about the journey.

I loved his voice; his simple, sardonic; hard, yet warm hearted slant.

Shoot Outs, Indians, Gold.

Blood and gore and greed;

Chilling, veterinarian like solutions;

No worries, they have a toothbrush.

I am still unsure how exactly; but Patrick deWitt took me on one helluva ride.

giddyup!

"All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing."

I remember a time not so long ago, at least not by my demographic.

A time when, what happened at home, stayed at home

You did not hang out your dirty laundry.

People did not talk about the unsavoury.

It wasn’t proper and it was not accepted.

Honour your father and your mother

Everybody has secrets, but

Only bad girls go to jail.

Backwoods noir, I know it and here it is.

Inspired by the true story of the Goler Clan of Nova Scotia, Our Daily Bread tells the story of The Erskines, who live on North Mountain, in poverty, secrecy and isolation. They deal in moonshine, marijuana and most recently the making and moving of meth.

Albert Erskine is one of their clan, but he is far from comfortable in his own skin or theirs. He yearns for a better life, a way to distance himself from these woods, the elders, their secrets.

Davis quickly brings the reader into the dark heart of these secrets without ever resorting to sensationalism. A glimpse is all that is needed.

Six year old club-footed Brenda, one of Lloyd’s kids, stood on an old bucket and looked in a back window. She wore a boy’s jacket over a filthy pink nightgown, a pair of rubber boots several sizes too large, to accommodate her twisted left foot. She’d been in need of a bath several weeks ago. Albert knew what she was probably seeing in there, and he knew if she got caught she’d get a worse beating than he just got. If he called out he’d just scare her and she’d make a noise and then they’d both be in for it. He should just walk away and let whatever was going to happen go right on and happen. Erskines don’t talk and Erskines better mind their own fucking business. She turned then and looked at him tears pouring down her face.

Time peeled away, fled backwards and Albert was six years old again, his mouth full, gagging, the stench and sound of moans, his own flesh tearing……..bile rushed acidly into his mouth. His hands shook. His knees shook. He turned away. Spit. Spit again. One of these days he was going to do it. He’d get his rifle and put and end to the Erskines, all of them.

Gideon, the town closest to North Mountain is full of God fearing people who shun The Erskine clan and the people of North Mountain. They believe them to be beyond salvation. Even so the people in Gideon have their own problems. Take Tom Evans, his marriage is in trouble, leaving his children Ivy and Bobby at odds, looking for their own solace.

When Albert Erskine, comes down off the mountain to fish, he runs into Tom’s teenage son Bobby, and an unlikely friendship develops. A friendship that is destined to set the people of North Mountain and Gideon on a collision course. One with devastating results.

Dorothy Carlisle is an independent minded widow who runs a local antique shop in Gideon. She is following a tradition, one once shared with her late husband, one of taking boxes of provisions: clothes, food, books and such, up to the mountain and leaving them in a secluded spot, hopefully, for the children to find.

Part of her very much did not want to hear the sound again. A voice in her head told her to get back in the car as quickly as possible, and lock the doors. She was aware of her own heartbeat, and of the blood pulsing in her veins. Crickets. A mosquito near her ear, which she forced herself not to swat. And then….

“Mmmuhuuh….mmmuhhaaaa”…..Bestial, but not the sound of an animal. Human. “Uuuhhuhhh.” Human made inhuman. A sort of low keening – bereft even of the hope anyone might hear. Dorothy’s skin prickled and tightened. The sound held no threat, but seemed to echo from an abyss of despair. Her horror was not of something red in tooth and claw, or even fist and blade. Rather, she recoiled from understanding. She feared for her soul if it peered into that abyss. As though under some hideous enchantment, Dorothy stared at her own trembling hand, unable to move. “Oh God, oh God, oh God. Protect us.”

The sound, the cry, came again then. Mourning made manifest. Such grief was surely as isolating, as solitary as any cell of stone or steel, as any nail and cross. Left to its own devices it would suck the entire world into the centre of its tarry core. It was alone out there.

This is the real deal. Read it.

2

2

1

1